Clean Architecture in Swift and SwiftUI: A Pragmatic Guide

Why another article about architecture?

Good question 😇. I can’t count how many articles about this have already been written, but… The best way to organize something in your own head is always to try putting it “on paper.” Then argue with yourself whether what you think you know is actually what it should be. Anyway… I felt a strong need to write down how I approach Clean Architecture. Basically what has worked over the years - small projects, big projects, sometimes over-engineered, sometimes over-simplified, but in the end - what needed to work, worked.

This article is my attempt to connect the dots. To show how Clean Architecture actually works with Swift and SwiftUI, without the cargo cult mentality that plagues our industry.

A few things upfront

MVVM is NOT architecture. I can’t stress this enough. MVVM is a presentation pattern - it describes how your View talks to your data. That’s it. You can’t build an entire application architecture on MVVM alone. Yet people do, and then wonder why their codebase turns into a mess.

Clean Architecture and Onion Architecture are not the same thing. Though they’re close relatives. Clean Architecture (Uncle Bob, 2012) evolved from Onion Architecture (Jeffrey Palermo, 2008). When we talk about Clean Architecture in iOS, we’re usually implementing Onion Architecture principles. Jeffrey Palermo deserves recognition for introducing the core concept of dependency inversion in layered architecture.

SwiftUI changed everything. And I mean everything. The patterns we used in UIKit don’t automatically transfer to SwiftUI. Actually, forcing UIKit patterns onto SwiftUI often means fighting the framework.

In all my own projects, I abandoned the ViewModel-per-View concept some time ago in favor of Stores (per feature/context). The idea isn’t new - Flux introduced centralized stores back in 2014, Redux refined it. Some now advocate for direct Model-View connection with @Observable, skipping any intermediate layer - but I find Stores provide the right balance between structure and simplicity.

Store vs ViewModel - the key difference:

- ViewModel: one per screen, holds state for that specific view, multiplies as your app grows

- Store: one per feature domain (Orders, Users, Settings), shared across multiple views, single source of truth

But whether you use ViewModel or Store - the Clean Architecture concept itself doesn’t change at all.

All code samples in this article are just examples to show the pattern and may be incomplete.

Part 1: The Foundation

What Clean Architecture Actually Is

Clean Architecture is not about specific patterns. It’s about principles:

- Independence of frameworks - Your business logic doesn’t know about SwiftUI, UIKit, or any Apple framework

- Testability - Business rules can be tested without UI, database, or external elements

- Independence of UI - The UI can change without changing the business rules

- Independence of database - Your business rules don’t know about persistence

- Independence of external agencies - Business rules don’t know about the outside world

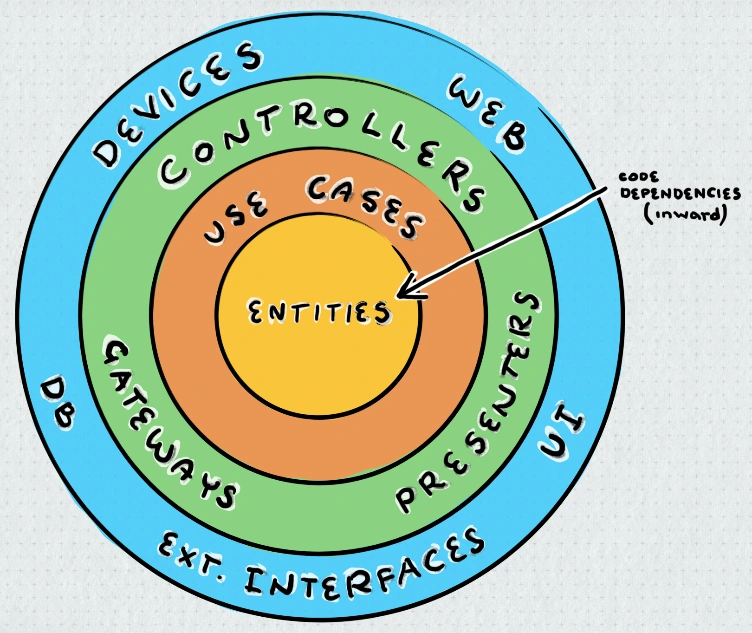

The famous circles diagram isn’t about specific layers - it’s about the Dependency Rule:

Source code dependencies can only point inward.

That’s it. The inner circles know nothing about outer circles. The Domain doesn’t know about the Data layer. The Data layer doesn’t know about the Presentation.

The Layers (Pragmatic Approach)

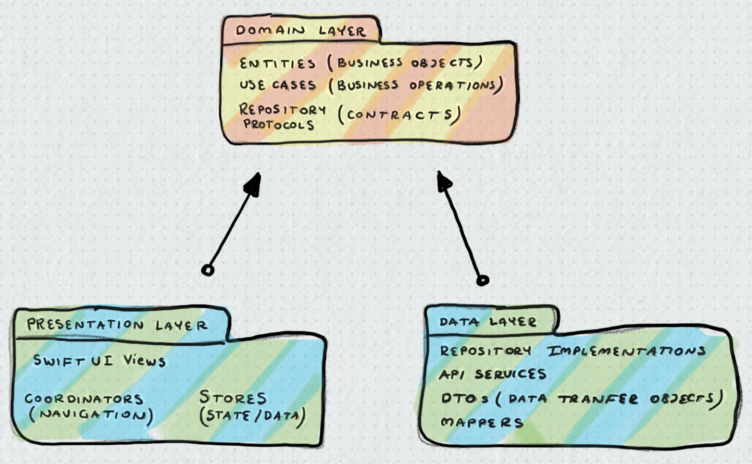

I’ve heard from many people that Clean Architecture presented as circles can be confusing. So I’ll try to draw the same thing below, but a bit differently 😉. Hopefully this will be clearer.

Critical insight: Your Store (or ViewModel, if you’re really stubborn and still need it) is not “between” layers. It’s fully in the Presentation Layer. It just happens to call things from the Domain layer. Store or ViewModel - they deal only with presentation logic: UI state, data formatting for display, handling user interactions. Business logic belongs in UseCases.

Part 2: The Domain Layer - The Heart of Your App

Why Domain Layer is Critical

The Domain layer is your app’s core. It’s pure Swift. No imports of SwiftUI, UIKit, Combine, or any framework. Just plain Swift.

// Domain Layer - pure Swift

struct User: Identifiable, Equatable {

let id: UUID

let email: String

let name: String

let subscription: Subscription?

var canAccessPremiumContent: Bool {

guard let subscription else { return false }

return subscription.isActive && subscription.tier.isPremium

}

}

This is a Domain Entity. It’s not a DTO. It’s not tied to JSON structure. It’s your business concept.

Entities vs DTOs

This is where many developers get confused.

DTOs (Data Transfer Objects) mirror external data structures - ugly, flat, tied to API:

// Data Layer - mirrors API response exactly

struct UserDTO: Codable {

let user_id: String

let email_address: String

let subscription_type: String // "free", "premium", "enterprise"

let subscription_active: Bool

let subscription_expires: String? // ISO8601 or null

}

Domain Entities represent your mental model - clean, typed, with behavior:

// Domain Layer - your business concepts

struct User: Identifiable, Equatable {

let id: UUID

let email: String

let subscription: Subscription

var canAccessPremiumContent: Bool {

subscription.isActive && subscription.tier.isPremium

}

// Nested type - Subscription only makes sense in User context

struct Subscription: Equatable {

let tier: Tier

let isActive: Bool

let expiresAt: Date?

enum Tier {

case free, premium, enterprise

var isPremium: Bool { self != .free }

}

}

}

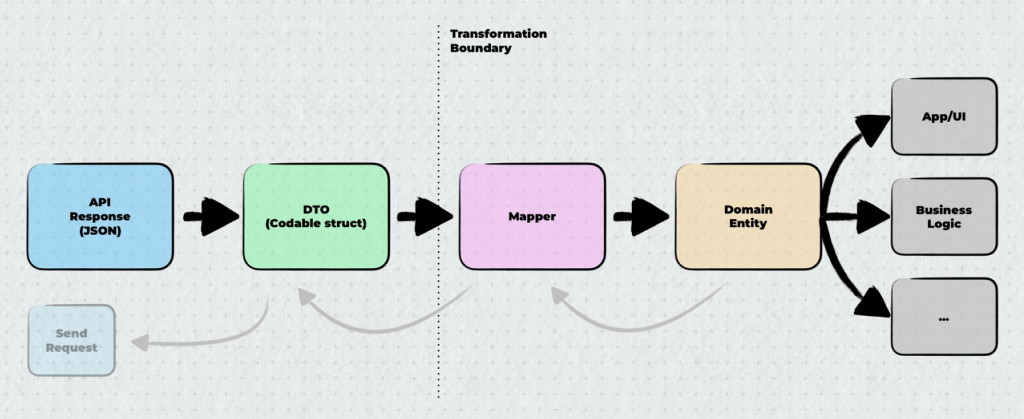

See the difference? DTO is flat strings and bools. Entity has proper types, enums, computed properties, nested structures. When API changes subscription_type from string to int - you fix one mapper, not your whole app.

Who does the mapping? The Repository Implementation. It sits in the Data layer, receives DTOs from APIs or databases, and converts them to Domain Entities before returning. When saving, it does the reverse - takes Domain Entities and maps them to DTOs. The rest of your app never sees DTOs - only clean Domain Entities.

Repository Protocols

Here’s where Dependency Inversion shines. The Domain layer defines what it needs through protocols:

// Domain Layer - the contract

protocol UserRepository {

func fetchUser(id: UUID) async throws -> User

func fetchUsers() async throws -> [User]

func save(_ user: User) async throws

}

Notice: this protocol knows nothing about URLSession, SwiftData, or any implementation detail. It works with Domain entities.

The implementation lives in the Data layer:

// Data Layer - the implementation

final class UserRepositoryImpl: UserRepository {

private let apiService: APIService

init(apiService: APIService) {

self.apiService = apiService

}

func fetchUser(id: UUID) async throws -> User {

let dto = try await apiService.get("/users/\(id.uuidString)")

return dto.toDomain() // Mapping happens here

}

func fetchUsers() async throws -> [User] {

let dtos: [UserDTO] = try await apiService.get("/users")

return dtos.map { $0.toDomain() }

}

func save(_ user: User) async throws {

let dto = UserDTO.from(user)

try await apiService.post("/users", body: dto)

}

}

Key point: The Data layer imports Domain layer. Domain knows nothing about Data.

Use Cases

It seems to me that the iOS world has always tried to play by its own rules (whether it made sense or not). For example, I rarely saw the concept of UseCase as a single business operation - if anything, it was grouping several operations together into <Name>UseCases, or <Name>BusinessLogic, or <Name>Manager, and you could probably find other variations out there. But the mental model remains the same - Use Cases (or Interactors) encapsulate business operations. More on this later, but… while abstraction is required at architectural boundaries, within the same layer we can but don’t have to create abstractions for UseCases - both protocol and implementation would live on the same layer anyway. So in short, Use Cases can be concrete classes, not protocols.

// Domain Layer - can be concrete class, no protocol needed

@MainActor

public final class MealUseCases {

private let repository: MealRepository // Repository IS a protocol - abstraction here

public init(repository: MealRepository) {

self.repository = repository

}

public func startNewMeal() async throws -> Meal {

let meal = Meal(timestamp: Date(), hungerLevel: 5)

try await repository.save(meal)

return meal

}

public func completeMeal(_ meal: Meal, rating: Int) async throws {

var updated = meal

updated.rating = rating

updated.completedAt = Date()

try await repository.update(updated)

}

}

Part 3: Protocol Strategy

The Dependency Rule Revisited

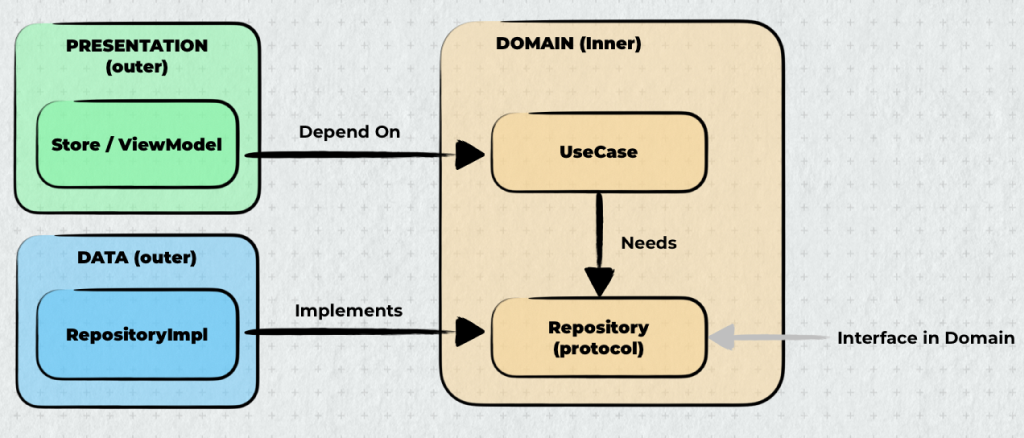

Protocols exist for one architectural purpose: inverting dependency direction.

The iOS community has developed a protocol addiction. “Protocol-Oriented Programming” got interpreted as “put protocols on everything.” But protocols have a cost - complexity, boilerplate, and in SwiftUI specifically, friction with @Observable and @Published.

The Clean Architecture Dependency Rule states:

Source code dependencies can only point inward.

When an inner layer needs an outer layer, we have a problem. The dependency would point outward. Protocols solve this by letting the inner layer define a contract that the outer layer implements.

When Protocols Are Mandatory

When inner layer needs outer layer - protocol must invert the dependency:

// Domain Layer - defines contract

protocol OrderRepository {

func fetchOrders() async throws -> [Order]

func save(_ order: Order) async throws

}

// Data Layer - implements contract

final class OrderRepositoryImpl: OrderRepository {

func fetchOrders() async throws -> [Order] { /* API call */ }

func save(_ order: Order) async throws { /* API call */ }

}

Without this protocol, Domain would import Data layer - violating the Dependency Rule.

When Protocols Are Optional

When outer layer calls inner layer - dependency already points inward:

// Store (Presentation) calls UseCase (Domain)

// Direction: outer → inner (Already correct)

@Observable

final class OrderStore {

private let useCases: OrderUseCases // Can be concrete class

}

You could add a protocol for decoupling or mocking, but it’s a choice - not an architectural requirement.

SwiftUI Friction

Beyond unnecessary complexity, protocol overuse in SwiftUI creates technical problems:

@Publishedproperties can’t be required by protocols@Observablemacro can’t be enforced via protocol - you cannot require a type to use@Observablethrough protocol conformance the way you could withObservableObject- maybe not critical here, but protocol existentials add indirection and potential heap allocations

The Simple Rule

| Dependency | Direction | Protocol Required? |

|---|---|---|

| Store → UseCase | Outer → Inner | No |

| UseCase → Repository | Inner → Outer | Yes |

In short:

- Inner needs outer → Protocol mandatory

- Outer calls inner → Protocol optional (often just overhead)

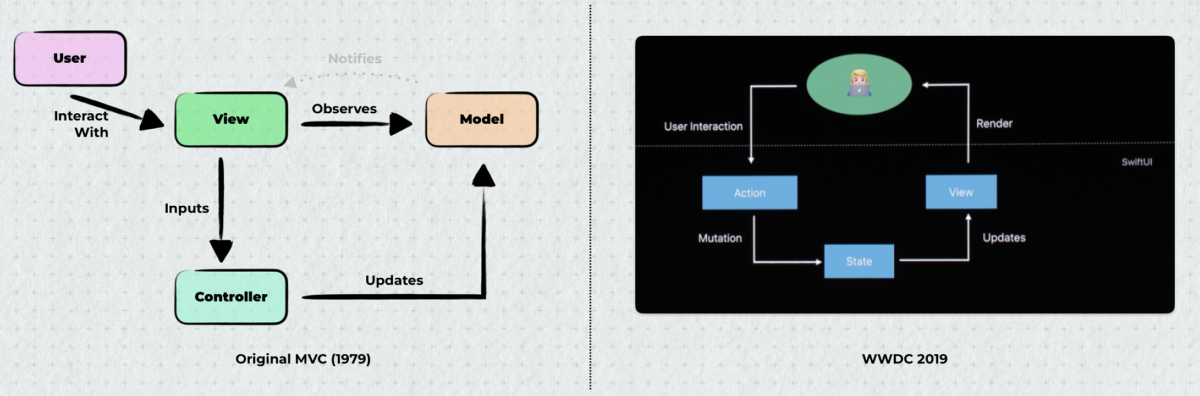

Part 4: SwiftUI and the Return to Original MVC

The Historical Context

Here’s something that blew my mind when I discovered it.

In 1979, Trygve Reenskaug created MVC at Xerox PARC. The original name was THING-MODEL-VIEW-EDITOR. Later renamed to Model-View-Controller.

The original MVC had a crucial characteristic that got lost over the decades:

The View directly observes the Model.

Not through a Controller. Not through a ViewModel. The View registered as a dependent of the Model - a mechanism later formalized as the Observer pattern in Krasner & Pope’s Smalltalk-80 MVC implementation. When the Model changed, it notified all Views automatically.

Sound familiar?

// SwiftUI

@Observable

class UserModel {

var name: String = ""

var email: String = ""

}

struct UserView: View {

var model: UserModel

var body: some View {

Text(model.name) // View directly observes Model

}

}

SwiftUI didn’t reinvent MVVM. It rediscovered original MVC.

Some time ago I heard the argument that SwiftUI’s View is basically a ViewModel. But that’s an oversimplification.

The @Observable / @State mechanism is essentially the Observer pattern that Reenskaug built into MVC 45 years ago. We went full circle.

Why This Matters for Clean Architecture

Reenskaug defined Model in his original 1979 paper:

“Models represent knowledge. There should be a one-to-one correspondence between the model and its parts on the one hand, and the represented world as perceived by the owner of the model on the other hand.”

He warned against mixing concerns:

“It is confusing and considered bad form to mix problem-oriented nodes (e.g., calendar appointments) with implementation details (e.g., paragraphs).”

Compare this to Uncle Bob’s Clean Architecture Entity:

“Entities encapsulate Enterprise wide business rules. An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions.”

The similarity is striking. Both represent the core “knowledge” of your application. Both insist on staying at the problem level. Both are decoupled from presentation concerns.

The key difference: Reenskaug’s Model was directly observable by Views. Clean Architecture’s Entity lives in the Domain layer, accessed through UseCases.

Where SwiftUI enters the picture.

Can you use Entities directly in SwiftUI Views? Absolutely - the dependency points inward. Can you call UseCases from Views? Technically yes. But here’s the constraint: Domain must stay pure Swift. No @Observable on Entities. No SwiftUI imports in UseCases.

This is where the Store concept fits. A Store sits in the Presentation layer where @Observable belongs. It holds domain state (the Entities returned from UseCases), manages loading/error states, and is shared across Views.

Store vs ViewModel: a critical distinction.

Martin Fowler’s Presentation Model (2004) - the basis for MVVM - defines ViewModel as:

“A fully self-contained class that represents all the data and behavior of the UI window… This won’t just include the contents of controls, but also things like whether or not they are enabled.”

ViewModel is the state of one View. One ViewModel per screen. It holds everything that screen needs - domain data plus UI state like isButtonEnabled, isSheetPresented, selectedTab.

Store is different. Flux and Redux introduced Stores as source of truth for domain state - shared across many views:

“This does not mean that every piece of state must go into the store! You should decide whether a piece of state belongs in the store or your UI components, based on where it’s needed.”

The separation is clean:

- Store: domain knowledge for a feature (orders, users, products) - shared, persists across navigation

- View’s @State: UI-local state (is sheet showing? is field focused?) - stays in the View

SwiftUI supports this naturally:

@Statefor view-local UI state - cheap, private, dies with the View@Observablefor Stores - shared domain state@Environmentinjects Stores down the hierarchy

With ViewModel-per-screen, you duplicate domain state across ViewModels and synchronize constantly. With Stores, domain state lives once, Views observe what they need, and @State handles the rest.

Clean Architecture doesn’t care how Presentation organizes itself. Domain must stay pure. Whether you use ViewModels, Stores, or something else - that’s an implementation detail within one layer.

Part 5: Implementing Stores

With the conceptual foundation in place, let’s look at implementation. A Store is organized by bounded context - one per feature domain:

// One Store per feature/domain area

@MainActor

@Observable

final class OrderStore {

private(set) var orders: [Order] = []

private(set) var isLoading = false

private(set) var error: Error?

// Store receives Repository protocol, creates UseCase internally

private let useCases: OrderUseCases

init(repository: OrderRepository) {

self.useCases = OrderUseCases(repository: repository)

}

func loadOrders() async {

isLoading = true

defer { isLoading = false }

do {

orders = try await useCases.fetchAll()

} catch {

self.error = error

}

}

func createOrder(_ draft: OrderDraft) async {

do {

let order = try await useCases.create(draft)

orders.append(order)

} catch {

self.error = error

}

}

}

Multiple Views can consume the same Store:

struct OrderListView: View {

@Environment(OrderStore.self) var store

var body: some View {

List(store.orders) { order in

OrderRow(order: order)

}

.task { await store.loadOrders() }

}

}

struct OrderDetailView: View {

@Environment(OrderStore.self) var store

let orderId: UUID

var order: Order? {

store.orders.first { $0.id == orderId }

}

var body: some View {

if let order {

OrderDetailContent(order: order)

}

}

}

Injecting Stores via Environment

SwiftUI’s Environment is perfect for dependency injection:

@main

struct ProsoPlateApp: App {

@State private var orderStore: OrderStore

@State private var userStore: UserStore

init() {

// Composition Root - wire dependencies here

let apiService = APIServiceImpl()

// Create Repository implementations (concrete classes)

let orderRepo = OrderRepositoryImpl(api: apiService)

let userRepo = UserRepositoryImpl(api: apiService)

// Create Stores with Repository protocols

// Stores instantiate UseCases internally

orderStore = OrderStore(repository: orderRepo)

userStore = UserStore(repository: userRepo)

}

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView()

.environment(orderStore)

.environment(userStore)

}

}

}

This init() is our Composition Root - a term popularized by Mark Seemann. It’s the single place where the entire dependency graph gets constructed. Repository implementations (Data layer) get created and passed to Stores (Presentation layer), which internally instantiate UseCases (Domain layer). Clean and simple.

In iOS apps, the Composition Root traditionally lived in AppDelegate or SceneDelegate. With SwiftUI, it naturally moves to the @main App struct. The key principle: compose as close to the entry point as possible, and let the rest of your app remain blissfully unaware of how things are wired.

Part 6: Project Organization with Namespaces

This builds on concepts from my previous article about Swift Namespaces and Code Organization.

Feature-Based Organization

Don’t organize by type:

❌ Bad structure:

├── ViewModels/

│ ├── OrderViewModel.swift

│ ├── UserViewModel.swift

│ └── ProductViewModel.swift

├── Views/

│ ├── OrderView.swift

│ ├── UserView.swift

│ └── ProductView.swift

├── Models/

│ ├── Order.swift

│ └── User.swift

Organize by feature:

✅ Good structure:

├── Features/

│ ├── Orders/

│ │ ├── Domain/

│ │ │ ├── Order.swift

│ │ │ └── OrderRepository.swift

│ │ ├── Data/

│ │ │ ├── OrderDTO.swift

│ │ │ └── OrderRepositoryImpl.swift

│ │ └── Presentation/

│ │ ├── OrderStore.swift

│ │ ├── OrderListView.swift

│ │ └── OrderDetailView.swift

│ └── Users/

│ ├── Domain/

│ ├── Data/

│ └── Presentation/

Cognitive psychology research supports this. Related code should be co-located. When you’re working on Orders, everything you need is in one place.

Namespaces with Caseless Enums

Swift lacks a namespace keyword. Use caseless enums:

enum Orders {

// Domain

struct Order: Identifiable {

let id: UUID

let items: [OrderItem]

let status: Status

enum Status {

case pending, confirmed, shipped, delivered

}

}

// Presentation

@Observable

final class Store {

private(set) var orders: [Order] = []

// ...

}

}

enum Users {

struct User: Identifiable {

let id: UUID

let name: String

}

@Observable

final class Store {

private(set) var currentUser: User?

// ...

}

}

// Usage is clean and discoverable

// (simplified - in practice Store requires dependencies, see Part 5)

let orderStore = Orders.Store(repository: orderRepo)

let user = Users.User(id: UUID(), name: "John")

Benefits:

- Xcode autocomplete: type

Orders.and see everything related - No name collisions

- Clear boundaries

- Apple does this (Combine’s

Publishersenum)

Part 7: DTOs and Mapping Strategy

Where Mapping Happens

Mapping from DTO to Domain entity happens in the Data layer:

// Data Layer

struct OrderDTO: Codable {

let order_id: String

let line_items: [LineItemDTO]

let status_code: Int

let created_timestamp: String

func toDomain() -> Orders.Order {

Orders.Order(

id: UUID(uuidString: order_id) ?? UUID(),

items: line_items.map { $0.toDomain() },

status: mapStatus(status_code),

createdAt: ISO8601DateFormatter().date(from: created_timestamp) ?? Date()

)

}

private func mapStatus(_ code: Int) -> Orders.Order.Status {

switch code {

case 0: return .pending

case 1: return .confirmed

case 2: return .shipped

case 3: return .delivered

default: return .pending

}

}

}

Validation at Boundaries

When data enters your system, validate it:

extension OrderDTO {

func toDomain() throws -> Orders.Order {

guard let uuid = UUID(uuidString: order_id) else {

throw MappingError.invalidId(order_id)

}

guard !line_items.isEmpty else {

throw MappingError.emptyOrder

}

guard let date = ISO8601DateFormatter().date(from: created_timestamp) else {

throw MappingError.invalidDate(created_timestamp)

}

return Orders.Order(

id: uuid,

items: try line_items.map { try $0.toDomain() },

status: mapStatus(status_code),

createdAt: date

)

}

}

Once data is in the Domain layer as an Entity, it’s already validated. The rest of your app can trust it.

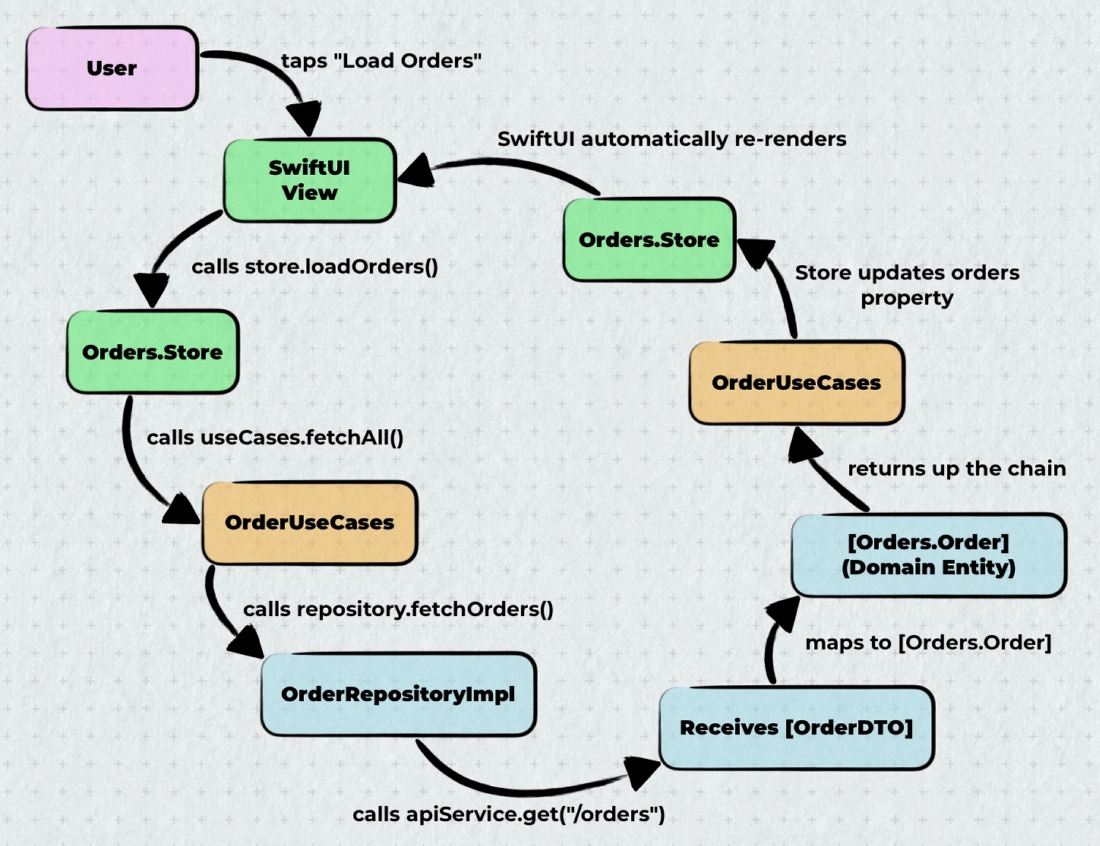

Part 8: The Complete Data Flow

The Complete Flow

Part 9: Testing Strategy

What to Test

Domain Layer - Test UseCases with mocked Repository. This is where protocols pay off:

final class OrderUseCasesTests: XCTestCase {

@MainActor

func test_fetchAll_returnsOrdersFromRepository() async throws {

// Given - mock the Repository protocol

let mockRepo = MockOrderRepository()

mockRepo.stubbedOrders = [.sample]

let useCases = OrderUseCases(repository: mockRepo)

// When

let orders = try await useCases.fetchAll()

// Then

XCTAssertEqual(orders.count, 1)

XCTAssertEqual(orders.first?.id, Orders.Order.sample.id)

}

}

Data Layer - Test mapping logic:

final class OrderDTOMappingTests: XCTestCase {

func test_toDomain_mapsCorrectly() throws {

// Given

let dto = OrderDTO(

order_id: "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000",

line_items: [],

status_code: 1, // 1 = confirmed

created_timestamp: "2024-01-15T10:30:00Z"

)

// When

let order = try dto.toDomain()

// Then

XCTAssertEqual(order.status, .confirmed)

}

func test_toDomain_throwsOnInvalidId() {

// Given

let dto = OrderDTO(order_id: "invalid", line_items: [], status_code: 0, created_timestamp: "")

// Then

XCTAssertThrowsError(try dto.toDomain())

}

}

Stores - Test with mocked Repository. The Store creates real UseCase internally - that’s fine, UseCase is just logic:

final class OrderStoreTests: XCTestCase {

@MainActor

func test_loadOrders_updatesState() async {

// Given - mock Repository, not UseCase

let mockRepo = MockOrderRepository()

mockRepo.stubbedOrders = [.sample]

let store = Orders.Store(repository: mockRepo)

// When

await store.loadOrders()

// Then

XCTAssertEqual(store.orders.count, 1)

XCTAssertFalse(store.isLoading)

XCTAssertNil(store.error)

}

}

Don’t Over-Test

You don’t need to test:

- SwiftUI views (use previews and manual testing)

- Trivial getters/setters

- Framework code

Focus on business logic and edge cases.

Summary: The Pragmatic Checklist

DO

✅ Keep Domain layer pure Swift - No framework imports

✅ Use Stores organized by feature - Not per-screen ViewModels

✅ Use protocols only to invert dependencies - Repository protocols yes, UseCase protocols rarely needed

✅ Use concrete types within layers - Stores, Views, Services

✅ Map DTOs to Domain entities at the boundary - Data layer responsibility

✅ Organize code by feature - Related code stays together

✅ Use namespaces - Caseless enums for clean organization

✅ Validate at boundaries - When data enters your system

✅ Start simple - Add complexity only when needed

DON’T

❌ Put business logic in Stores/ViewModels - That belongs in Domain layer

❌ Create protocols for everything - Only where you need to invert dependency direction

❌ Add UseCase protocols “for testing” - Mock Repository instead, test UseCase with real logic

❌ Let Views call Repositories directly - Go through Stores and Use Cases

❌ Use DTOs throughout the app - Map to Domain entities early

❌ Organize by type - Feature-based is more maintainable

❌ Fight SwiftUI’s data flow - Embrace @Observable and Environment

❌ Over-engineer simple features - Pragmatism over pattern purity

The Golden Rule

Your architecture should scream what your app does, not what framework you’re using.

When someone opens your project, they should see Orders/, Users/, Products/ - not ViewModels/, Services/, Managers/.

Conclusion

Clean Architecture in Swift and SwiftUI isn’t about following patterns blindly. It’s about principles:

- Dependencies point inward - Domain doesn’t know about anything else

- Separate concerns - Each layer has its job

- Test business logic - Domain layer is easy to test because it’s pure Swift

- Embrace SwiftUI - Don’t fight the framework with UIKit patterns

The patterns I’ve shown here work in production. They scale. They’re testable. And they don’t require fighting the framework.

Start simple. Add complexity when you need it. And always ask yourself: “Does this make the code easier to understand and maintain?”

If the answer is no, you’re probably over-engineering. 🤗